ARNHEM BRIDGE AREA |

|

| During 18-19

September, most of the Hohenstaufen's available armour, joined by the Kampfgruppe Knaust

launched heavy attacks from the north-east. Eventually pinned down by superior numbers of

infantry, Frost's battalion was reduced by artillery, and the concentrated fire of the

SP's and tanks who were able to roam virtually at will. On the bridge at Arnhem on the 19th and 20th the defenders were continually attacked, shelled and mortared. The houses which they were holding were set on fire, food and ammunition ran low, and the numbers of wounded continually mounted. Nevertheless the position was still held. However by the evening of the 20th nearly all the houses held had been set on fire and there was nowhere to put the wounded. During the night enemy infiltration made the position worse. At about the time that John Frost was wounded, the bridge force lost one of its most important positions. In the substantial Van Limburg Stirum School building, halfway along the eastern side of the ramp embankment running down to the town, the combined force of Royal Engineers and 3rd Battalion men who had held this exposed position throughout the battle, with no heavier weapon than a Bren gun, were about to be overwhelmed. About thirty men remained unwounded, but ammunition was low and there was no food or water.

Captain Mackay returned to the building to fetch out the remainder of the rearguard. The intention now was for the whole party to move to a nearby building, the one evacuated by the Royal Engineers on the Sunday night. Men were being hit outside the school, and Major Lewis called out from his mattress: 'Time to put up the white flag'. Some men being unwounded, felt guilty about allowing themselfes to be captured, so they called out to ask if the fit men could attempt to get out. He shouted back that they could. This news was passed to the RE' s. About ten men, including Captains Robinson and Mackay, then dashed across the road into the gardens of some houses to the east, only to be discovered later and taken prisoner. (Mackay eventually escaped and reached England). A sapper was sent to the top of the embankment with a

white towel tied to his rifle but was immediately struck on both legs by a burst of

machine-gun fire. He died of those wounds five months later. The Germans closed in, and

the firing ceased. So ended the gallant defense of the Van Limburg Stirum School. |

OOSTERBEEK PERIMETER |

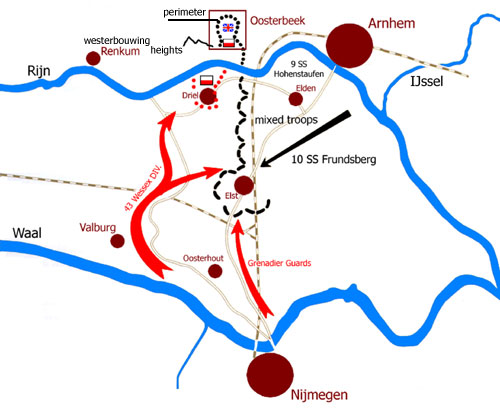

| At nine o'clock on the morning of the 21st September, General Urquhart held a conference at his Headquarters to organize a defensive perimeter of those troops that remained. These were divided into two forces, one under Brigadier Hicks, the other under Brigadier Hackett. They were to hold a position with its base on the river Rhine, and running from the area of Oosterbeek Church northwards across the main road to Arnhem to the neighbourhood of Graftombe, thence its western flank passed a few hundred yards west of the Hartenstein Hotel to Heveadorp. This position during the battle did contract and individual enemy troops were to infiltrate into, but despite intense German efforts it never gave way. |

| 1st POLISH INDEPENDENT PARACHUTE BRIGADE GROUP |

|

| It is now necessary

to recount the activities of the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade Group. Its anti-tank battery

had landed in gliders in the midst of the battle on the 18th and 19th September and been

absorbed into the 1st Airborne Division on the north side of the river. Because of the

altered course of the events, the Brigade itself could not be dropped on the 19th

September as planned. It was clear also that it could not carry out its original task of

landing south of the main Arnhem bridge, crossing it and occupying a position east of

Arnhem. A dropping zone was therefore selected for the Poles east and north-east of Driel

on which they landed on the evening of 21st September with the task of holding a firm

bridgehead on the south bank of the river in that area.

That night their patrols found that the Heveadorp ferry had been sunk and that the north bank of the river at that point was in enemy hands, meantime during the 20th and 21st enemy attacks on the Divisional perimeter had been continuous and the whole area was being submitted to an intense bombardment by every kind of shell, mortar and bomb the enemy possessed. Hand to hand fighting with enemy infantry and close range engagements with enemy gun and flamethrowing tanks were frequent occurrences. It was imperative that if the British Second Army were to take advantage of this small remaining bridgehead on the north bank of the river they should do so immediately. Reinforcement of the perimeter was also essential if it was to remain of sufficient size to cover a crossing of the river in force. However it was only by the night of 20th September that a gallant operation by the British Guards Armoured Division and the American 82nd Airborne Division had succeeded in capturing the bridge at Nijmegen, and despite all efforts made it was not until the evening of the 23rd September that the 43rd British Infantry Division succeeded in reaching the south bank of the river west of Driel in force. They were too late for any major crossing to be attempted that night. Nevertheless efforts had been made on the night of the 22nd September to get as many of the Polish Parachute Brigade as possible across the river from south to north. As a result of enemy action and a shortage of boats or rafts only some 50 men got over. The following night the Polish Parachute Brigade again tried to cross the river in force and, after many casualties, they ferried over a further 200 officers and men.

But his superiors saw it all different. He was ignored and at the Valburg conference became clear that the British Commanders were allready looking for a scapegoat. It was decided that a Battalion of the Dorset Regiment and 1st Battalion of the Polish Brigade would try to cross the river under command of XXX Corps. Sosabowski made clear that there was absolutely no chance of success to cross the river on that spot where the Germans were in control of the higher grounds on the opposite bank of the river. He was ignored and send away in a very unpolite way. So on the nigth of the 24th September the 4th Battalion The Dorset Regiment of the 43rd British Infantry Division made a attempt to cross the river led by their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel G. Tilly. There were not enough boates for the 1st Polish Battalion. The landings were very scattered owing to enemy fire and the swift river current, and the battalion was never able to concentrate on landing. It was a total failure and a waste of troops and the outcome made no difference at all. For the detailed story on the Allied betrayal of the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade Group and its Commander General Stanislaw F. Sosabowski and an overview of all its KIA with data and photo's we recommend the book 'All Men Are Brothers' published by our Foundation in the year 2005. As a result of this book the Brigade got awarded the highest Dutch military decoration (Military Order of William or Militaire Willemsorde). Also General Sosabowski was awarded the highest Dutch decoration for bravery (Bronze Lion or Bronzen Leeuw) posthumously. The Medal ceremonies took place in Den Haag in 2006 where the decorations were awarded by Her Royal Highness Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. (foto report available in the photo gallery) |

MULTIMEDIA ADDITIONS TO THIS PAGE |

| Veterans Memories: Lt. Jerzy

H. Dyrda Veterans Memories: Obergefreiter Heinz Ackermann Veterans Memories: Lance Corporal Slawomir Kwiatkowski |

Either a German tank standing on the ramp only

seventy yards away or a German gun further away started systematically blowing away the

roof and top store of the building, where most of the defenders were positioned. One shell

set the roof ablaze; another burst where two of the 3rd Battalion officers, Major Lewis

and Lieutenant Wright, were taking their turns to rest, injuring both officers. What did

happen next became an emotive subject among the defenders. There were no means of putting

out the fire, and it was obvious that the building had to be evacuated. Captain Mackay

appointed a party of sappers to remain at their positions to prevent any German attack

over the surrounding ground while the evacuation took place. The wounded were brought up

from the basement, the eight seriously hurt being carried on doors or mattresses.

Meanwhile, the shelling of the upper part of the building had continued, and one of the

rearguard positions was hit with two men being killed and one badly crushed.

Either a German tank standing on the ramp only

seventy yards away or a German gun further away started systematically blowing away the

roof and top store of the building, where most of the defenders were positioned. One shell

set the roof ablaze; another burst where two of the 3rd Battalion officers, Major Lewis

and Lieutenant Wright, were taking their turns to rest, injuring both officers. What did

happen next became an emotive subject among the defenders. There were no means of putting

out the fire, and it was obvious that the building had to be evacuated. Captain Mackay

appointed a party of sappers to remain at their positions to prevent any German attack

over the surrounding ground while the evacuation took place. The wounded were brought up

from the basement, the eight seriously hurt being carried on doors or mattresses.

Meanwhile, the shelling of the upper part of the building had continued, and one of the

rearguard positions was hit with two men being killed and one badly crushed.  During the flight a radio message came in that the group had to

return because of bad weather. 2/3 of the Armada turned home but Sosabowski ordered his

group to keep flying. Therefore the Polish Brigade landed at Driel without the heavy

weapons and only at 1/3 of it's strenght and with no up-to-date information or

intelligence on the situation. Beside that they landed in occupied territory and during

the landing they were shot at from all sites. It was a miracle that only few casualties

occured during the landing.

During the flight a radio message came in that the group had to

return because of bad weather. 2/3 of the Armada turned home but Sosabowski ordered his

group to keep flying. Therefore the Polish Brigade landed at Driel without the heavy

weapons and only at 1/3 of it's strenght and with no up-to-date information or

intelligence on the situation. Beside that they landed in occupied territory and during

the landing they were shot at from all sites. It was a miracle that only few casualties

occured during the landing. Sosabowski was a very expirienced officer. He

had fought against the Germans in 1939 when Poland was invaded and was one of the few

commanders who was still booking succes against the Germans when the battle in Poland was

allready lost. Sosabowksi analysed the situation. He still saw a change to turn the tide

in favour of the allies. A major crossing downstream close to Wageningen would offer the

opportunity to attack the Germans in the back and rescue the remainder of 1st Airborne

Divison and also establish a bridgehead further upstream.

Sosabowski was a very expirienced officer. He

had fought against the Germans in 1939 when Poland was invaded and was one of the few

commanders who was still booking succes against the Germans when the battle in Poland was

allready lost. Sosabowksi analysed the situation. He still saw a change to turn the tide

in favour of the allies. A major crossing downstream close to Wageningen would offer the

opportunity to attack the Germans in the back and rescue the remainder of 1st Airborne

Divison and also establish a bridgehead further upstream.