Name: A.J. (Tonny) Gieling

Rank: Civillian

Unit: Red Cross Volunteer

I was 22 years old and a keeper at Burgers Zoo. It was

the morning of Sunday 17 September and I was on my way home to the boarding-house at 12

Kastanjelaan, when British bombers suddenly appeared over the city and bombs began to

fall. A bomb had already fallen in the Bloemstraat and there were dead and wounded German

soldiers lying in the street in front of the Café. A badly burnt rabbit dashed across the

road in front of me and disappeared. At the end of the Bloemstraat, there was a young boy

whose legs were trapped under the stairs of a burning house. I stopped and helped some

other passers-by to free him.

I was 22 years old and a keeper at Burgers Zoo. It was

the morning of Sunday 17 September and I was on my way home to the boarding-house at 12

Kastanjelaan, when British bombers suddenly appeared over the city and bombs began to

fall. A bomb had already fallen in the Bloemstraat and there were dead and wounded German

soldiers lying in the street in front of the Café. A badly burnt rabbit dashed across the

road in front of me and disappeared. At the end of the Bloemstraat, there was a young boy

whose legs were trapped under the stairs of a burning house. I stopped and helped some

other passers-by to free him.

Once I got home, I started to explore the neighbourhood. Some houses in the Johannastraat had also been hit. The target for the bombs had probably been the Menno van Coehoorn barracks, but several bombs had destroyed houses in the area. To this day this is an open space in the city. A badly wounded man was being helped onto a stretcher. I took one end of the stretcher and ran with it via the Klarendalsweg - Willensplain - Utrechtseweg to the Elisabeth Gasthuis hospital. On arrival, it turned out that the man was already dead. He was moved to the mortuary and I never did learn his name. I remained at the hospital to help as a Red Cross assistant. It marked the start of a series of shocking, disturbing and intense experiences that were really too much for a 22-year old. There seemed to be a sense of unreality to most of them, and I could scarcely comprehend the magnitude and seriousness of what I was caught up in.

There were rumours everywhere that we had been liberated and I was a witness to the first British soldier that entered the hospital. He crept along the edge of the garden and stopped at the main entrance to the hospital. I stared at him in amazement and in particular at the Walkie Talkie he was carrying. I’d never seen anything like it! I couldn’t speak a word of English, but the nurses rushed up to him and hugged and kissed him. Free at last!! From the conversation that followed, I understood that he couldn’t wait and that he had to move on. He used the Walkie Talkie continuously. One of the nurses told me that he had asked for the garden gate to be unlocked so that he could move on to the city centre. The key could not be found and the soldier left, moving onto the Utrechtseweg. As he stepped into the road he was shot and killed by one of a group of Germans who had hidden behind the trees. A second British soldier moved to the body and picked up the radio, but he too was killed further down the street.

Wounded British troops started arriving at the hospital. A number of British doctors also appeared including Lt. Col Townsend, Maj Longland, Lt. Allenby and Maj Lippmann Kessel. Despite not understanding the conversation, I was full of admiration for these brave men who stood talking to the Dutch doctors, Schaap, Stuyt and van Hengel. Suddenly they burst into the British national anthem followed by the Dutch national anthem which was even accompanied by one of the British officers! While they were singing, a British soldier appeared with his rifle in the back of a German officer. It turned out that the German was a surgeon and he stood to attention until the anthems drew to a close. After a brief discussion, he was pressed into service in the hospital and accepted as a fellow member of the medical staff. It was an odd collection of British and Dutch doctors, a German surgeon, German nuns, Dutch and English nurses, resistance fighters and a group of voluntary Red Cross assistants, who would be responsible for caring for the wounded that would flood the hospital.

I was asked to help the wounded as they arrived at the hospital. My job was to complete the necessary papers, shave and clean the area around the wound with pikrine- zuur. Tens of wounded were on stretchers on the floor. If someone with a stomach injury arrived I had to warn the doctors so that they received priority. A number of Dutch SS soldiers were also brought in, one of which had been hit in the stomach. He came from Deventer and he told me that he had been caught in a trench with his unit at Schoonoord (Oosterbeek). When he had volunteered to go for water he had been hit by a sniper. When I asked him if I should contact his family later to explain what had happened, he told me that it was not necessary as he had fought for a good cause. A day after his operation, I saw him in a bed in a ward that had been hit by a shell and the ceiling had collapsed. He was still alive but not long afterwards his eyes closed and he died.

The hospital was taking regular hits from artillery shells by this time. One round flew through the front of the building and ripped through the head of a patient as he was being fed by a German nun. She sat there staring with the plate still in her hand.. It all passed me as a flood of unreality. So much happened to me in such a short time that I simply could not absorb and assimilate it all.

From this point I can’t remember what exactly happened, until I recall that I was asked to ride with a lorry full of British soldiers, to guide them to the bridge. We drove very slowly and it hardly seemed like there was a war on. When we arrived at the Velperplein, we saw a unit of German soldiers moving past the Apeldoornseweg. No-one fired on us and we in turn also fired on no-one. I can’t recall why, but we returned to the hospital without firing a single shot and without reaching the bridge.

In the evening of the 17th September, I was instructed to accompany a British soldier and some others to the Rijnhotel, which was close by. By this time it was dark and there were a number of fires burning in the centre of Arnhem. Next to the hotel lay a number of British dead. We were too late for them. We had turned to return to the hospital when we heard a number of vehicles approaching. We hid between the trees and waited for them. They stopped close to our position and we could hear them talking together. They were Germans. One of the British soldiers threw a hand grenade towards the group and it was devastatingly effective. The few survivors fled into the hospital. On entering the hospital I heard Jaap Stuyt, who was wearing a white doctor’s coat, shouting at the Germans that there would be no fighting in the hospital as it contravened the Geneva Convention. The Germans surrendered their weapons and they were led away to the basement where they were put under guard by one of the British.

Ward 34 was assigned to us, the Red Cross assistants. This is where our group, including Bert and Hans Kuik, Hessel Prinsen, Gerard Schreuder, Henk van Kuipers and Frans Wiessing, could rest and try and make sense of the incredible events that we had witnessed during the day. It all seemed so unreal. Doktor Stuyt asked me to accompany him to his house to collect some things. Once at his villa, we went down to the cellar and I was amazed to find it full of bottles of wine. It seemed incredible that in such a situation, in the middle of a war, with so much suffering and shortages, such luxury could have survived, I took as many bottles as I could carry and retuned to the hospital. Later I went to the home of Doktor Van Hengel and collected a number of boxes of cigars.

In the meantime, I had obtained a motorcycle and I was

asked, together with Sister de Lange dressed in Red Cross clothes, to deliver messages to

amongst others the family Bossevain in Velp. Sister de Lange was killed after the battle

for Arnhem when a bomb fell close by as she cycled on the Velperweg.

In the meantime, I had obtained a motorcycle and I was

asked, together with Sister de Lange dressed in Red Cross clothes, to deliver messages to

amongst others the family Bossevain in Velp. Sister de Lange was killed after the battle

for Arnhem when a bomb fell close by as she cycled on the Velperweg.

During one of my trips on the motorcycle accompanied by Henk van Kuipers, he heard artillery fire coming from the south and he jumped off the bike. Shortly afterwards I heard a loud explosion and tumbled off the bike. The rear wheel was completely blown away and I thought I’d wet myself, but it turned out to be blood from a shrapnel wound in my backside. I tried to scramble to my feet but a German voice shouted for me to stay down. Then the Germans started to fire over my head. I’d strayed into the front line of the battle. When there was a lull in the firing, Henk rushed over to me with a couple of others and laid me out on a stretcher, on which I was carried back to the hospital. Fortunately the injury was not serious and the splinter was removed and the wound cleaned and dressed.

I lay in the corridor next to a woman who asked continuously if it was day or night and the time of day. She told me that she couldn’t see anything. She lived in Doorwerth. During the fighting a Polish soldier wearing a British uniform had suddenly appeared at their home. He was greeted warmly and offered any assistance that was possible. The man started to take an unhealthy interest in her grand-daughter and started trying to force himself on her. The woman’s husband offered the soldier jewellery if he left them alone, but he dragged the girl outside. In a voice broken with sobs, the woman told me that she ran desperately after them and once outside was hit by the shell splinters that had blinded her. The story made a deep impression on me and I promised to report it as soon as I could, but as a result of the terrible developments that were to came, nothing could be done.

My injuries were not serious and I was soon back in action at the hospital. Due to my experience at the zoo, I was asked to assist with the removal of shell splinters from the backside of a horse! I also had to slaughter a pig as the cooks in the kitchen couldn’t manage it themselves. During the operation on the horse, I started to feel unwell and I passed out. Dr. Hengel diagnosed acute appendicitis. I had to be operated on the next day. But as I had seen so many operations and was concerned about possible infections, I refused the operation, saying that I felt much better. In the evening I joined in the meal that had been created from the pig, but the pain suddenly returned and I was taken directly to the operating theatre for an appendectomy.

I recovered amazingly quickly and was soon back at work in the hospital. One day a German tank could be seen travelling very slowly towards us from the centre of the city. He stopped in front of the hospital and trained the gun on us. The turret opened and a German in a black uniform climbed out, shouting that he wanted to see the director immediately. He claimed that someone had shot at him from the hospital. Hospital workers ran inside to find the director, but he couldn’t be located. The German became very impatient and threatened to blow up the complete building if the director didn’t show up immediately. Suddenly our German surgeon appeared from the hospital and explained to the soldier that he had been well treated and that no-one had fired on the tank. The surgeon persuaded the German soldier to continue on his way and he left slowly on towards Oosterbeek. Unfortunately the surgeon also left in our last ambulance!

After the battle, we, the Red Cross personnel, were one of the few groups that remained when the

city was evacuated. We were forced to help the SS with the identification and burial of

the dead.

After the battle, we, the Red Cross personnel, were one of the few groups that remained when the

city was evacuated. We were forced to help the SS with the identification and burial of

the dead.

I witnessed terrible things. In one house I found a dead man and woman sitting under a table, locked in an embrace.

When we arrived in Oosterbeek, on the corner of Dreyenseweg with the van Limburg Stirumweg, there were bodies everywhere. The German soldiers took anything of value.

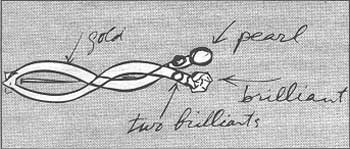

One of the bodies caught my eye as there were no visible wounds. I could not determine how this young lieutenant had died. The others had all been almost cut to pieces by the gunfire. When I opened the jacket of this man, I noticed a gold pin over his heart. If I had left it I knew that the Germans would steal it, so I slipped it into the top of my boot for safekeeping, along with his papers and a photo of his wife. This was very dangerous as I wouldn’t have been spared if I had been caught.

A few days later it became clear that we were in danger as it became known that the Red Cross had helped the Allied troops. I fled to Nunspeet, but during the journey I lost the lieutenant’s photo and papers. The pin was safely attached to my sweater. The pin and the memory of the soldier who had been wearing it continued to haunt me. It became a symbol of the many brave British soldiers who had tried to liberate us and paid the ultimate price. In 1952 I moved to the Antilles and the pin went with me along with the memories of the spot in Oosterbeek where I had found it. During a visit back home in the Netherlands, I left the pin at the Airborne Museum in the hope that a visitor would recognise it. Every six years I would return to the Netherlands and visit the Museum to see if the pin had been claimed, but the damn pin was always there to greet me. In 1977 I returned to the Netherlands permanently and I read an article in the local newspaper about Mr. Tiemens who was trying to identify missing soldiers. I asked for his assistance and gave him a detailed description of the young lieutenant, the photo of his wife and of course the pin. Tiemens knew exactly which units had fought at that spot and contacted Major Pott to tell him that a lieutenant of his had been killed there. Major Pott contacted Mrs. Watling, the wife of the dead lieutenant.

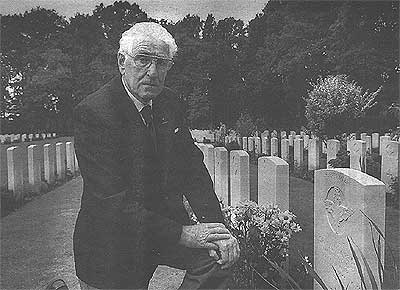

Mrs. Watling responded directly to the letter and the drawing of the pin. She said that it was her hatpin, which she thought she had lost. She had never known that her husband had taken it with him when they had been together for the last time, probably as a good luck charm. As a result of this, the remains of Lt. Watling have been identified and he has his own headstone at the cemetery at Oosterbeek. Mrs Watling and her three children came to Oosterbeek in February for the memorial ceremony. There I returned the pin to her after 50 years. The family can at last place flowers at the grave of their husband and father. When she took the pin, Mrs. Watling said 'The book is now closed'.

Editor: The drawing of the pin that was recognized by Mrs. Watling.

The retired policeman and ex-lion tamer Ton Gieling is now (2003) 81 years old and lives in Oosterbeek. It turns out that I have lived for 20 years less than 100 meters from him.

The record of Lt. Stanley Watling in the Digital Monument

Back to the other veterans memories