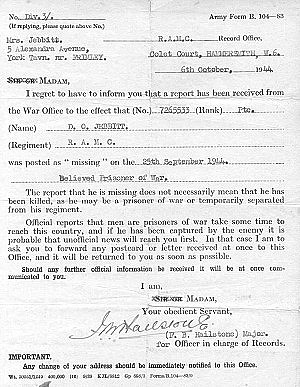

Name: David Jebbitt

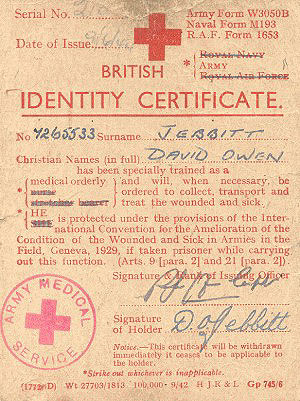

Rank: Medical Orderly

Unit: 181st Field Ambulance

Regiment: Royal Army Medical Corps

I was part of the first lift of the operation, which took place on 17th September 1944. He flew in a Horsa Glider

(towed by a Dakota) from Down Ampney Airfield in Gloucestershire and landed at the drop

zone near Wolfheze outside of Oosterbeek. As part of the 181st Field ambulance, I was

based at the main dressing station in the Schoonoord hotel (Oosterbeek). Casualties were

heavy and medical supplies short and I soon found myself taking over the role of

anaesthetist, under the direction of one of the surgeons. Amputations were carried out

using saws issued for POW escape purposes and these were little more than hacksaw blades.

The fighting was house-to-house and at close quarters and quite often the Germans would be

right across the street, so stepping outside, even for a moment, to collect casualties was

always dangerous.

I was part of the first lift of the operation, which took place on 17th September 1944. He flew in a Horsa Glider

(towed by a Dakota) from Down Ampney Airfield in Gloucestershire and landed at the drop

zone near Wolfheze outside of Oosterbeek. As part of the 181st Field ambulance, I was

based at the main dressing station in the Schoonoord hotel (Oosterbeek). Casualties were

heavy and medical supplies short and I soon found myself taking over the role of

anaesthetist, under the direction of one of the surgeons. Amputations were carried out

using saws issued for POW escape purposes and these were little more than hacksaw blades.

The fighting was house-to-house and at close quarters and quite often the Germans would be

right across the street, so stepping outside, even for a moment, to collect casualties was

always dangerous.

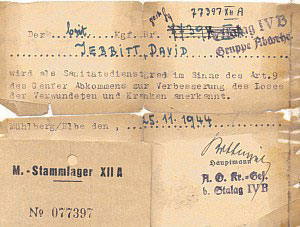

By Sunday the 24th (having held out since their arrival on the 17th) the wounded numbered over 1,200. Medical teams were working under horrendous conditions and the hotel was targeted several times with mortars. Being caught up in the centre of the fighting, the dressing stations were inevitably being drawn into the line of fire and finally a truce was agreed with the Germans on humanitarian grounds and the wounded evacuated to a German hospital. The R.A.M.C. medical staff remained behind and were first taken to the Dutch army barracks at Apeldoon before being taken by train to East Germany (Muhlberg on Elbe) to a German prisoner of war camp.

The following account, detailing my journey back from the camp, was written by me in 1954, as part of a writing course. It is interesting in that it shows just how wary the allies already were of the threat posed by the Russian advance. After the war, I remained in the RAMC and eventually rose to the rank of Colonel.

Muhlberg on Elbe was the site of Stalag IVB during the years we were at war

with Germany. It was there that I was moved as a very reluctant guest of the third Reich

after being captured in Holland. However, my stay was not so long as expected and three

months later, after a night of constant rattle of gunfire, we awoke to find that all the

German guards had fled from the advancing Russian army. That was a joyous day indeed,

especially for those who had been less fortunate than I, and had spent periods of up to

four years in the camp.

Muhlberg on Elbe was the site of Stalag IVB during the years we were at war

with Germany. It was there that I was moved as a very reluctant guest of the third Reich

after being captured in Holland. However, my stay was not so long as expected and three

months later, after a night of constant rattle of gunfire, we awoke to find that all the

German guards had fled from the advancing Russian army. That was a joyous day indeed,

especially for those who had been less fortunate than I, and had spent periods of up to

four years in the camp.

After the first few hours of daylight things settled down. The order was given by the Russians that we remain in the camp, for ‘mopping up’ was still in progress in the near vicinity and a few thousand ex-POWs milling around outside might complicate matters. I returned to my hut and rested up on my bed for a spot of happy contemplation now that for us the war was over.

The W.O. in charge of my hut came over to me and asked if I’d like to go up to the German Lazarette. The Russians were moving all their sick from the camp to the Lazerette and would like some help in looking after them. I should get a decent bed up there and the thought of exchanging my louse ridden straw mattress for a decent one was too good a bribe to refuse.

A couple of other volunteers joined us at the gate and we were escorted to a small group of wooden buildings, about a mile up the road, outside the camp.A room recently vacated by the late camp guards was made available for us. We dumped our few personal belongings and tried out the springs of the three beds in the room. We were sure of a good nights sleep for the few nights we were to be there. The W.O. had assured us that we would stay only until the Russians joined up with the Americans and a route back to England was available for us.

The first week went by and we had no complaints. We fed at the kitchen with the Russians, and although nothing fancy appeared in the fare, it was solid and substantial and certainly an improvement on what we had been existing on. The patients we looked after were mostly suffering from malnutrition, as the Russians had no Red Cross parcels to supplement their prison food.

Our duties consisted of helping to make the beds, wash the floors, and fetch the patients’ food from the kitchens.

There was one Russian doctor and about half a dozen Russian uniformed girls who carried out the nursing duties.

A fortnight after we had been moved up to the Lazerette, the British and American ex-prisoners of the camp were moved out by

American lorries, the Americans having joined up with the Russians at the Elbe. We got ready to join them.

Our duties consisted of helping to make the beds, wash the floors, and fetch the patients’ food from the kitchens.

There was one Russian doctor and about half a dozen Russian uniformed girls who carried out the nursing duties.

A fortnight after we had been moved up to the Lazerette, the British and American ex-prisoners of the camp were moved out by

American lorries, the Americans having joined up with the Russians at the Elbe. We got ready to join them.

Our expectancy was short lived. We were told that permission had been obtained for us to stay behind for a couple of days until further Russian reinforcements arrived to help out. We would then be taken down to the American lines and handed over for repatriation. A little dismayed, we returned to our work. The Russians appeared to be friendly, although actual conversation was invariably carried out in a broken German, which was not very good on either side. For the next couple of days we carried on as before. The floor washing was beginning to become rather tedious, for our Russian friends seemed to obtain a humourous satisfaction from watching us on our hands and knees every day. The excuse of reinforcements was also beginning to appear a bit thin. Lounging around were quite a number of fawn smocked Russians, sporting hammer and sickle cap badges, who would be equally capable of floor scrubbing. Another week went by and still, daily, we were presented with buckets of hot water, disinfectant and scrubbing brushes.

Our numerous enquiries about when we were to be escorted to the American lines did not produce a satisfactory reply, so we decided

that scrubbing was out until we knew exactly where we stood and the day we were to be

repatriated. In a mixture of English, German and sign language, we conveyed to the

Russian officer that we were going on strike, but we received no satisfaction. That

night, after our evening meal, we returned to our room and decided that we would take

matters into our own hands, that if the Russians would not take us to the Elbe we would

make our own way there.

Our numerous enquiries about when we were to be escorted to the American lines did not produce a satisfactory reply, so we decided

that scrubbing was out until we knew exactly where we stood and the day we were to be

repatriated. In a mixture of English, German and sign language, we conveyed to the

Russian officer that we were going on strike, but we received no satisfaction. That

night, after our evening meal, we returned to our room and decided that we would take

matters into our own hands, that if the Russians would not take us to the Elbe we would

make our own way there.

The following day we stocked up with bread and odd scraps salvaged form the kitchen and each with a haversack, prepared for our journey. By now the Russians attitude left open to doubt that should we be found moving off, we might be forcibly detained. We would therefore leave that night. Our packed haversacks were carefully smuggled out and hidden in a clump of bushes about a hundred yards down the road. After dark we sauntered out of the building and strolled casually down the grass verge of the roadside. Behind the bushes we collected our haversacks and struck out across the fields, the moonlight was sufficient to show us our way. We had a rough idea of the direction to take. We decided to keep clear of the roads until we were well clear of the camp. We know that we could circle around the outside of the town of Muhlberg and that the river Elbe lay on the other side. We had only then to follow the course of the Elbe until we came to a bridge, cross over and place ourselves in the hands of the first Americans we came across. We kept going until early dawn and covered about fifteen to twenty miles, until the town of Muhlberg was behind us.

As dawn rose we decided to find a place to sleep. An old farm building in the distance seemed to be the most suitable place. There was only an old farmer in occupation when we arrived. After we had told him who we were he seemed very glad of our company. His opinion of the Russians expressed as 'Ruskie nix good'. Most of the German population had fled across the Elbe from the advancing Russians, who, so the farmer said, had looted everything of value during their advance. Our German host prepared us a hot stew. Afterwards we slept off the weariness of our nights journey. Shortly after mid-day we awoke and decided that we would push on ahead for the American lines.

The farmer prepared us a cup of coffee and bid us farewell. On the road towards Reisa we caught up with a German woman who was pushing a small wooden trolley with all her worldly possessions piled on top. She recognised us as English and begged that we take her with us to the Americans. As she spoke a certain amount of English we felt that her help as interpreter would be useful and we agreed. We piled our haversacks onto the trolley and taking it in turns to push the cart, continued our journey. The road we were on seemed endless. A few trucks passed us but nobody stopped to enquire who we were. Our journey took us through one or two villages, but they had been reduced to ghost towns and all the occupied houses had large red flags hanging down from the windows to comply with Russian orders. Very few Germans remained on the streets. Occasional movements behind drawn curtains told us that frightened people were trying to catch a glimpse of their future fate.

As night approached the German woman said she knew some people in the next town in whose house we could spend

the night.

The following day we moved off towards the Elbe. The German woman told us there was a bridge across the river two miles away. She herself had decided to remain with the doctor. After walking for about half an hour along the main road we came to the bridge. We saw a small wooden hut at the side of the entrance and a wooden pole placed on two trestles straddled the road. An armed Russian sentry was standing outside the hut and another guard was pacing the bridge to the centre, the other half of the bridge being patrolled by an American.

We indicated to the Russian outside the hut that we were British

and wished to cross over the bridge. He disappeared inside and emerged again accompanied

by an officer. Shortly afterward a US officer, seeing our predicament, came across and

conferred with the Russians. The American was very pleasant. He shook hands with us,

saying that we would soon be on our way home, but first the Russians wanted proof of our

identity before they would let us cross the bridge. This was quite easy: we had our pay

books and stalag identity cards. After scrutinising them, the Russian officer handed

them back and shouted a command to the sentry. We were allowed to cross.

We indicated to the Russian outside the hut that we were British

and wished to cross over the bridge. He disappeared inside and emerged again accompanied

by an officer. Shortly afterward a US officer, seeing our predicament, came across and

conferred with the Russians. The American was very pleasant. He shook hands with us,

saying that we would soon be on our way home, but first the Russians wanted proof of our

identity before they would let us cross the bridge. This was quite easy: we had our pay

books and stalag identity cards. After scrutinising them, the Russian officer handed

them back and shouted a command to the sentry. We were allowed to cross.

The American officer hastily obtained a jeep and we were taken to their barracks to be flown home to England the following day. While waiting for the jeep to arrive we chatted to the Americans on guard at the bridge. They all had a pretty poor opinion of their Russian allies. One even said that he would have been quite willing to have continued the advance right through to Moscow. It distinctly remains in my memory that he commented 'It’ll save us the job in ten years time' his ten years prophesy are up in May of this year.