Name: Norman Howes

Rank: Sergeant

Unit: 10 Platoon, 'A' Company 2nd Battalion

Regiment: South Staffordshire Regiment

In 1942 I volunteered for the new

Airborne troops and was sent to the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, on

transfer from the Royal Fusiliers, where I served with them in North Africa, the invasion

of Sicily (where we sustained almost 50% casualties) and Italy. We returned to Woodhall

Spa, in England, in December 1943 and prepared for the invasion of Europe. After D-Day

there were a number of occasions when we were put on readiness for operations in support

of the rapid Allied advance, including "Operation Comet", where my platoon was

tasked with crash landing on an anti aircraft unit at the southern end of Arnhem bridge. I

have often wondered how different the outcome would have been if that operation had

proceeded. We took off for Arnhem , as part of the second lift, from Broadwell on the

morning of 18th September. This was not a popular decision amongst the men as by now the

Germans knew that we were coming, why else were the DZs being defended, and anticipated

that we would encounter a lot of anti aircraft fire on our approach. In the event the

journey was uneventful although, as expected, we received a high amount of anti aircraft

and small arms fire on our approach but, fortunately, sustained only minimal casualties

and losing only one glider. We landed at about 3 o'clock and were immediately sent to join

the remainder of the Battalion at the "Monastery" about 400 yards from St

Elizabeth's Hospital. (This we later learned was actually the Town Museum)

In 1942 I volunteered for the new

Airborne troops and was sent to the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, on

transfer from the Royal Fusiliers, where I served with them in North Africa, the invasion

of Sicily (where we sustained almost 50% casualties) and Italy. We returned to Woodhall

Spa, in England, in December 1943 and prepared for the invasion of Europe. After D-Day

there were a number of occasions when we were put on readiness for operations in support

of the rapid Allied advance, including "Operation Comet", where my platoon was

tasked with crash landing on an anti aircraft unit at the southern end of Arnhem bridge. I

have often wondered how different the outcome would have been if that operation had

proceeded. We took off for Arnhem , as part of the second lift, from Broadwell on the

morning of 18th September. This was not a popular decision amongst the men as by now the

Germans knew that we were coming, why else were the DZs being defended, and anticipated

that we would encounter a lot of anti aircraft fire on our approach. In the event the

journey was uneventful although, as expected, we received a high amount of anti aircraft

and small arms fire on our approach but, fortunately, sustained only minimal casualties

and losing only one glider. We landed at about 3 o'clock and were immediately sent to join

the remainder of the Battalion at the "Monastery" about 400 yards from St

Elizabeth's Hospital. (This we later learned was actually the Town Museum)

My Company ('A' Company) took the lead and very shortly after leaving the DZ we captured a German Hauptman. I made some remark to a soldier about "Getting the bastard back to HQ" when, in perfect English, he rebuked me for my language. On my obvious astonishment he remarked that he used to be a Director of a Cotton Mill in Oldham (England) and added that they had known that we were coming but did not know our landing places - "Now we know that", he warned, "God help you". During the initial part of our journey to join the Battalion we experienced slight sniping and "air burst" shelling but sustained only light casualties. However, as we approached the "Monastery" (museum) and the Hospital we saw many Airborne dead in the roadway, here we started encountering much heavier opposition and were required to fight hard to get through to the leading units.. On finally reaching the Battalion's forward positions in the early hours I took position with my platoon on the 1st floor of the "Monastery" . There was some probing by tanks during the night which were supported by well sighted enemy machine guns in the nearby houses. We retaliated with Piats but with minimal effect. We had no other anti tank guns to repel these attacks.

Fighting continued hard throughout the morning and about 10 o'clock I went downstairs to confirm ammunition supply with CSM Vic Williams. On climbing the stairs to return to my platoon I found that our position had been overrun and occupied by SS troops. I noted that they were very young. Instinctively I threw myself back down the stairs and managed to find shelter behind an upright piano which protected me from the inevitable grenade which followed. I fired at the two soldiers that came after it, killing one and possibly wounding the other, and managed to escape into the corridor, warning the others (including the Dutch civilians still sheltering there) that the Germans were in the building.

Almost immediately the building was again subjected to an attack by tanks

but this time the position was overrun. In company with a soldier from a parachute

regiment I managed to escape and started back towards the pavilion, about 300 yards away,

where RSM Slater directed us down to the lower road towards where the railway bridge

crosses the road. Here 'S' Company had formed the defensive position in an area known as

'Acacialaan'. It was at this location that John Baskeyfield won his VC. On the way we

found a jeep, complete with Vickers Machine Gun and loaded trailer, in the possession of

two Germans. We regained possession of this valuable item and, on arrival, handed it over

to Major Buchanan, Officer commanding Support Company.

Almost immediately the building was again subjected to an attack by tanks

but this time the position was overrun. In company with a soldier from a parachute

regiment I managed to escape and started back towards the pavilion, about 300 yards away,

where RSM Slater directed us down to the lower road towards where the railway bridge

crosses the road. Here 'S' Company had formed the defensive position in an area known as

'Acacialaan'. It was at this location that John Baskeyfield won his VC. On the way we

found a jeep, complete with Vickers Machine Gun and loaded trailer, in the possession of

two Germans. We regained possession of this valuable item and, on arrival, handed it over

to Major Buchanan, Officer commanding Support Company.

I noted his disappointment when I advised him that I was not a machine gunner. After becoming involved in a heavy firefight at this position I took position in a slit trench just south of the church as part of "Lonsdale Force". Here I remained for the next 4 or 5 days, time had no meaning and the days just rolled into one another. We endured very heavy shelling and consistent machine gun fire. The position was overlooked from the heights of Westerbouwing from whence we encountered very accurate small arms fire. Very heavy casualties were sustained, primarily from the constant mortar fire. We found that the German infantry were not prepared to attack on their own, likewise the tanks were unwilling to attack without infantry support, but, together, they became a determined and very effective unit, making frequent probing attacks. On the last day the Lonsdale Force did rear guard action to the evacuation, the South Staffords, in turn, did rear guard to the Lonsdale force. My group was therefore amongst the last fifty to leave and, consequently, by the time I reached the river I found myself part of a column 8 wide and about 400 yards long all waiting for boats to ferry us across the river. As daylight came we came into view of the German troops on Westerbouwing and started to come under mortar and machine gun fire. Despite this discipline remained high and everybody stood in silence, waiting their turn and passing the wounded forward to ensure that they were evacuated. I remember actually envying these men their wounds About 8 o'clock an officer came along the line giving permission to surrender or make our own way across the river. I decided to take a chance and attempt to escape across the river.

By this time the area where the

boats were crossing was receiving very heavy mortar and machine gun fire so I decided to

make my way downriver away from the bridge and the main crossing point. I couldn't believe

my luck when, just around the bend in the river, I found a small rowing boat about 8 foot

long, in good condition, but without oars or rowlocks. In the prow was an old kapok life

jacket. Being a poor swimmer I took off my equipment and put it on. I was quickly joined

by three other soldiers and we set off across the river rowing with helmets, hands and

rifle buts. We made good progress and soon approached the opposite bank. Unfortunately the

current was much too strong and we found ourselves being swirled in and out of the groynes

making it impossible to land. We came under fire and one of the men was hit. Next a burst

of machine gun fire hit us and we were all thrown into the water. I was swept back into

midstream and I was able to see the others struggling to reach the bank. I could hear one

of them shouting that he couldn't swim. I was carried downstream past the enemy positions

on Westerbouwing and again came under fire. Then I caught on the stern of a sunken boat,

which I later learned was the Driel ferry, and took shelter behind the wheel house. After

a short while I dropped down onto the sand and ran up the beach, taking shelter in a small

hollow just below the embankment. Unfortunately a machine gunner on the opposite bank had

seen me and commenced to "dig me out". I was saved by the very timely

intervention of two RAF Typhoons patrolling the river. These encouraged the Germans to

stop firing and "go to ground" giving me the opportunity to climb up over the

embankment and into relative safety. I was later picked up by a patrolling tank and taken

to an artillery unit who gave me a bowl of porridge, my first proper food for seven days.

From here I was taken by lorry to Nijmegen.

By this time the area where the

boats were crossing was receiving very heavy mortar and machine gun fire so I decided to

make my way downriver away from the bridge and the main crossing point. I couldn't believe

my luck when, just around the bend in the river, I found a small rowing boat about 8 foot

long, in good condition, but without oars or rowlocks. In the prow was an old kapok life

jacket. Being a poor swimmer I took off my equipment and put it on. I was quickly joined

by three other soldiers and we set off across the river rowing with helmets, hands and

rifle buts. We made good progress and soon approached the opposite bank. Unfortunately the

current was much too strong and we found ourselves being swirled in and out of the groynes

making it impossible to land. We came under fire and one of the men was hit. Next a burst

of machine gun fire hit us and we were all thrown into the water. I was swept back into

midstream and I was able to see the others struggling to reach the bank. I could hear one

of them shouting that he couldn't swim. I was carried downstream past the enemy positions

on Westerbouwing and again came under fire. Then I caught on the stern of a sunken boat,

which I later learned was the Driel ferry, and took shelter behind the wheel house. After

a short while I dropped down onto the sand and ran up the beach, taking shelter in a small

hollow just below the embankment. Unfortunately a machine gunner on the opposite bank had

seen me and commenced to "dig me out". I was saved by the very timely

intervention of two RAF Typhoons patrolling the river. These encouraged the Germans to

stop firing and "go to ground" giving me the opportunity to climb up over the

embankment and into relative safety. I was later picked up by a patrolling tank and taken

to an artillery unit who gave me a bowl of porridge, my first proper food for seven days.

From here I was taken by lorry to Nijmegen.

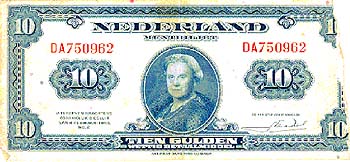

Exhaustion caught up with me and I remember very little of this journey. At Nijmegen we were billeted in an old school where we were issued with rifle and ammunition. The seabourne tail had arrived and made themselves comfortable in the safety of the basement. We were allocated billets on the floors above where we were quite vulnerable to the air raid that came during the night. Here I met the survivors of my unit. Of the 767 South Staffords that went into Arnhem there were just 124 left. Of the 120 men of "A" Company there were just five, myself, L/Cpl Brearley and Privates Pattison, Stone and Williams. A short time later, back at Woodhall Spa, we each signed a 10 Guilder Liberation Note that I had carried with me throughout the battle.

Editor: Norman Howes went to Arnhem in 1998 for the last time. He died on January 3rd, 2000.